Narrating Oil:

Energy Transitions in British Literature

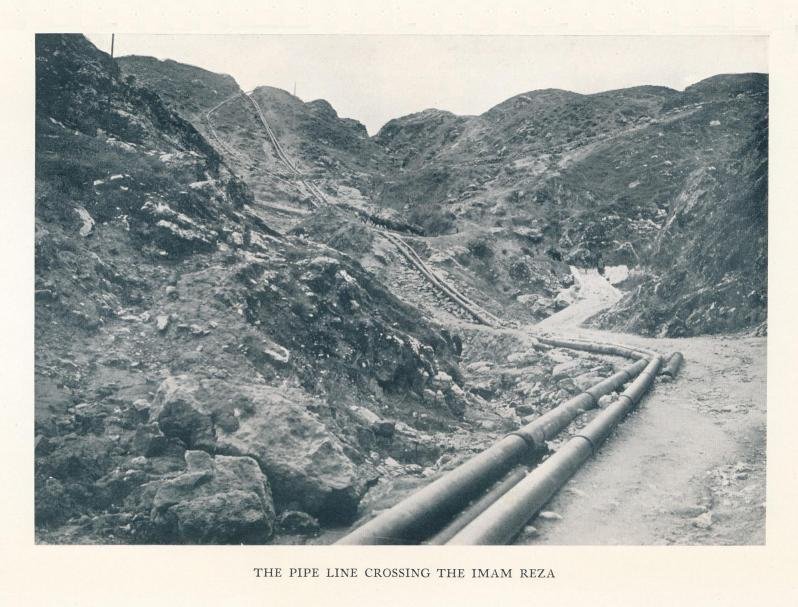

Image: Photograph from Vita Sackville-West’s Twelve Days, published by The Hogarth Press in 1928.

What are the narratives we tell ourselves about oil?

How has oil shaped the British cultural imaginary?

And can innovations in literary narratives help re-frame our relationship with fossil fuels as we transition towards a decarbonised future?

Oil poses unique challenges to literary representation, with its materiality, production and consumption resisting straightforward depiction. Throughout modern and contemporary British literary history, writers have developed new narrative strategies to tell the story of oil, its ascendency and its transformative effects. This new research project brings to light how writers are drawn to specific prose forms and genres (the travelogue, novel, drama and memoir) to interrogate the ecological, aesthetic and socio-political consequences of the extraction, production and consumption of oil.

The Project

The rise of oil in Britain, broadly coterminous with literary modernism, necessitated a turn away from earlier forms of narrative (such as the nineteenth-century ‘coal novel’) and a willingness to innovate modes of expression that could convey oil’s unique material and social properties. The early twentieth century was a period in which Britain played a decisive role in establishing global markets for oil, while in the second half of the century domestic oil production in Scotland supplemented Britain’s global influence. This project will show how oil sparked a series of literary experiments that can be traced through modernism, late modernism and contemporary literature.

In doing so, this will be the first major project focused on how oil produced a discernible modern and contemporary British literary history. It will show how literary works are both shaped by oil and, in turn, influence how we imagine, understand and use oil, demonstrating how by attending to literary form we can better understand the dynamic relationship between energy sources and cultural discourse. As such, this is a project that will not only offer a new theoretically sophisticated account of literary and environmental history but will contribute to urgent debates around global fuel insecurity, climate change and the lived experience of national energy policies.

The project is built around a historical narrative. When the Royal Navy transitioned from coal to oil in 1900, its production became a political as well as economic priority, with the British government investing in oil exploration in Persia. For Vita Sackville-West, who describes a trip to the Persian oil fields in Twelve Days (1928), the ‘clanking, belching settlement’ is at once fascinating and alarming. For Sackville-West, and other modernist writers such as Virginia Woolf, the travelogue presented itself as a form that could be re-moulded to articulate the story of oil: how and where it was produced, how it was transforming colonial politics, and the cost to environments and individual lives, both in Britain and overseas. In the same period, other modernists were being drawn into close proximity with oil companies through commissioned work. From Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell’s artworks for Shell to Dylan Thomas’s work as a filmscript writer for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, oil was seeping into the form and materiality of modernist works.

By the mid-century, global oil production was a key contributor to the ‘Great Acceleration’ of industrial production and emissions, while from 1964 onwards commercial offshore production of North Sea oil presented another threshold moment, with the social and environmental consequences of oil production felt by communities in Scotland. These shifting geopolitical and environmental moments again prompted British writers to reassess the narrative forms through which they might critically respond to and depict how oil was reshaping daily life, at both an individual and national level.

For writers such as J.G. Ballard, turning to and reshaping earlier modernist writing on oil offered a way of exploring how the substance was seeping into human subjectivity, blurring the distinction between organic human life and inhuman energy forms. Inspired by figures such as the Italian Futurist F. T. Marinetti, whose manifesto imagined the future transformations that might come from imbibing oil itself, Ballard’s Crash (1973) looked to capture the transformative fluidity of this crude new world. While earlier modernist novelists also looked to oil as a source of positive or negative influence, including D. H. Lawrence, who was influenced by Marinetti to purge ‘the old forms and sentimentalities’ of the novel in The Rainbow (1915), in works such as Crash we see the acceleration in the oil cultures of post-war Britain and a formal acceleration that pushes the modernist novel to its furthest limits.

At the same time, post-war Scotland was witnessing a wave of writers reworking narrative forms in order to capture a collective and communal expression of oil’s impact when it becomes a domestic product. In Bill Forsyth’s film focused on the threat of North Sea oil to a small coastal community, Local Hero (1983), the use of narrative tropes from classical Hollywood films parallel Britain’s wholesale adoption of top-down American models of oil production. In the same period, John McGrath’s The Cheviot, The Stag and the Black, Black Oil (1973) established the degree to which experimental and modernist drama could also speak to the complex issues that arise from the entanglement of environmental and economic factors attached to North Sea oil, establishing a dramatic mode that has been taken up in more recent works by British playwrights writing about oil, such as Ella Hickson’s Oil (2016) and Ben Harrison’s Crude (2016).

Now, in a moment of energy transition again, as Britain looks to wean itself off oil, writers are once more revising how we tell the story of oil. Homing in on the memoir as a genre accommodable to the complexity of our present, memoirists such as Tabitha Lasley and Sue Jane Taylor can be found responding to the economic and personal pull that oil continues to exert despite the environmental and political necessities of a decarbonised future.

Image: Vanessa Bell, Alfriston, 1931.

Image: Grangemouth Refinery, near Edinburgh, August 2023. Copyright Peter Adkins.

Image: Oil rig graveyard, Invergordon (joiseyshowaa / Creative Commons)